PART ONE. Seeking Communitas & Liminality

April 2, 2020

This is Victor and Edith Turner.

They are the authorities on ritual. Their work on rites of passage, of initiation, and of transition are classics of cultural anthropology.

In our confusion, I found myself pulling their books down from my shelf.

I am planning on spending my pandemic with the Turners and the ideas they have given us: Liminality & Communitas

My hope is that they will help me see the opportunity that we have been given to shape our future.

For we are most certainly in a transition - a reset; and how we act now can either limit or expand our possibilities.

Victor Turner & Liminality

“Limen” is Latin for threshold.

Liminality is the transformative state of being in-between.

Building on the work of Van Gennep, Victor Turner saw rites of passage (or transition) as countercultural sources of transformation.

Change is brought about by separating from the Structure of everyday life, to a state of Anti-Structure to a place of possibility:

"The attributes of liminality are necessarily ambiguous....Liminal entities are neither here nor there, they are betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom, convention and ceremonial.”

It’s what comes after what we have been, and before what we will finally become.

He called this Anti-Structure the "mother of all invention."

Right now we are in a collective rite of transition - where our future is being invented.

A man is jogging at a pace slower than walking, with black earphones plugged into a radio.

He looks absolutely exhausted, but not like he has been running.

He will not make eye contact.

Must be a pandemic tourist from New York.

I saw him with a mask going into the corner store the night before.

Edith Turner & Communitas

Communitas is the name given by Victor Turner to the experience of collective joy that happens in the liminal or threshold phase of a rite of passage.

Edith Turner continued her husband’s work in a book on the lived experience of the threshold, “Communitas, The Anthropology of Collective Joy” in 2011:

“What is communitas? The characteristics of communitas show it to be almost beyond strict definition, with almost endless variations. Communitas often appear unexpectedly. It has to do with the sense felt by a group of people when their life together takes on full meaning…Communitas can only be conveyed through stories.”

We can see communitas come alive now in response to the coronavirus. George Monbiot captures the spirit here:

A thousand books and films and business fables assure us that the fairytale ending to which we should all aspire is to become a millionaire. Then we can isolate ourselves from society in a mansion with high walls, with private healthcare, private education and a private jet. The commons envisages the opposite outcome: finding meaning, purpose and satisfaction by working together to enhance the lives of all. In times of crisis, we rediscover our social nature.

And as Charles Eisenstein writes in his wonderful essay, “The Coronation:”

Perhaps the great diseases of civilization have quickened our biological and cultural evolution, bestowing key genetic information and offering both individual and collective initiation. Could the current pandemic be just that? Novel RNA codes are spreading from human to human, imbuing us with new genetic information; at the same time, we are receiving other, esoteric, “codes” that ride the back of the biological ones, disrupting our narratives and systems in the same way that an illness disrupts bodily physiology. The phenomenon follows the template of initiation: separation from normality, followed by a dilemma, breakdown, or ordeal, followed (if it is to be complete) by reintegration and celebration.

Now the question arises: Initiation into what?

Me & The Turners

I find so much pleasure in the idea of the Turners, it surprises me.

In 1964, the husband develops a structure explaining human experience (based on fieldwork his whole family participated in) that makes room for anti-structure, and publishes academic essays, papers and lectures.

In 2011, the wife becomes the primary advocate for the actual experience of the anti-structure and publishes a book that seeks, not to explain, but to immerse in a collection of personal narratives.

Is there nothing more beautiful?

My plan is to continue to read and think and write about the Turner’s, their books and our pandemic.

I intend on doing this in a far more personal way than I am accustommed to, or comfortable doing.

I do this (or say I’m going to do this) because, well, I have never done it before.

Thank you for reading.

Peter

PART TWO. Zoom, Awkwardness & False Communitas

April 9, 2020

Leaving my house this morning for a walk with my daughter, I greeted my neighbor Caroline, four houses down.

“How are you?” She asked.

“I don’t know!” I yelled with a laugh, throwing my hands in the air. “You?”

“I’m the happiest I’ve ever been!” She said. “Crazy, right?”

Last week, I quit a facilitation workshop after about ten minutes. I had paid for it, and there was absolutely nothing wrong with it.

I imagined my exit as an act of defiance. It was a reflex, though, really.

Stubborn and petulant. Scared.

At the moment I left, the facilitator (who is great) was assuring us that real connection was possible through zoom.

I couldn’t take my eyes off of myself among 12 strangers on my desktop.

Then, he shared a trick.

His hand reached off the top of the screen, and pulled back to reveal a sticky note – with a smiley face on in it.

By placing it next to the camera on his computer, he was reminded to look into the camera. And, by looking into the camera, viewers would experience the near illusion of eye contact.

He had hacked human connection!

My cursor raced to click “Leave meeting.”

I was out. I couldn’t quite handle the awkwardness. And I love awkwardness.

As a researcher, The Awkward is my workplace. So I consider myself pretty intrepid.

But there is a difference between zoom awkwardness and real awkwardness.

Real awkwardness is that space between people that we must turn towards, for when we do, we are almost always met.

It’s noise, that we must brave, to pierce through to the signal of connection.

Zoom awkwardness is a lie.

Or, more accurately, zoom awkwardness is a truth that we feel we must deny. It’s signal, that we tend to ignore, settling for the empty approximation of connection.

The word ‘Awkward’ is made up of two contradicatory directions: “back-handed” + “turned toward.”

If we were to heed the awkwardness, we would turn the right way around, toward another person for connection.

The Danger of False Communitas

The first chapter of Edith Turner’s book “Communitas” is about the difference between true and false communitas.

And the first story is about babies.

In the late 1970s, Colwyn Trevarthen, a neurologist from Edinburgh studied the interaction between babies and their mothers, using live and recorded video.

In some sessions, they allow mother and baby in separate rooms to interact by way of live video. In others, they play a recorded video of the mother for the baby.

And in others, they play a recorded video of the baby for the mother.

“We can picture what happens when the mother waves in the non-synchronized showing. The child does not wave back. There is no eye contact. The timing is wrong and the baby becomes puzzled and distressed. What has happened is the communitas of interaction between mother and child is lost. The baby has been presented a false communitas - and apparently by its own mother. Babies can recognize the real thing when it comes, and its opposite…Travarthen draws the conclusion that the faculty of recognition of the genuine is innate.”

The rest of the chapter is devoted to stories of False Communitas or, the Negation of Genuine Communitas.

In one, a hiking guide kills spontaneity with forced questions. In another, a bank manager tries to induce communitas in a ‘morning employee huddle.’ And another, a survivor of Hurricane Katrina recounts how the police worked against communitas.

Each story adds a layer to what we know about communitas. “The sense cannot be fully put into words.”

The hope is, clearly, that we will become able to identify it ourselves, and preserve it.

Our neighbor Ed is a pastor.

Walking home with my daughter, Ed asks us to wait for him.

I feel trapped, and nervous as he crosses the street to where we are standing.

He gives us a blessing, from too close. As he leaves, he apologizes for having gloves on. “I don’t know what to do.”

“We love you,” I say as we part.

The phenomonology of videoconferencing

The phenomenologist Norm Friesen studies education technology. Among the reasons he identified that videoconferencing is “too bizarre to be natural” were the lack of eye contact and embodied reciprocity.

“In eye contact, you not only observe the eyes of the other person,” observes author and philosophy professor Beata Stawarska, but this other person is also “attending to your attention while you are attending to hers.”

This extends to multiple levels of awareness, as philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty observes: “I look at him. He sees that I look at him. I see that he sees it. He sees that I see that he sees it.” Merleau-Ponty adds that as a result, “there are no longer two consciousnesses” in a moment of locked eye contact, “but two mutually enfolding glances.”

Ursula LeGuin & Amoeba Sex

In the above quotes, I hear echoes of Ursula LeGuin’s glorious essay, “Telling is Listening.” In it, she blesses us with two images of how listening works.

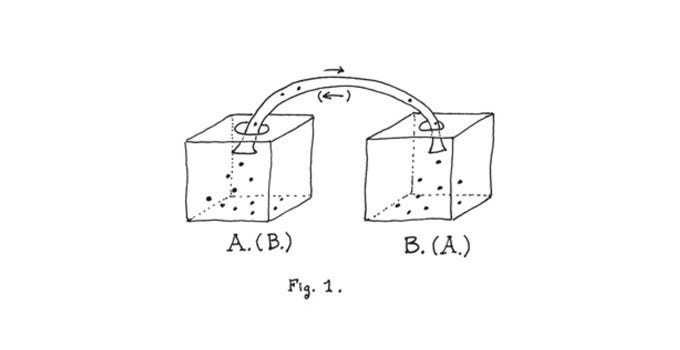

The first, the dominant view, is a transmission of information from one container to another.

In most cases of people actually talking to one another, human communication cannot be reduced to information. The message not only involves, it is, a relationship between speaker and hearer. The medium in which the message is embedded is immensely complex, infinitely more than a code: it is a language, a function of a society, a culture, in which the language, the speaker, and the hearer are all embedded.

The second, her own image for actual human conversation, is amoeba sex.

Amoeba A and amoeba B exchange genetic “information,” that is, they literally give each other inner bits of their bodies, via a channel or bridge which is made out of outer bits of their bodies. They hang out for quite a while sending bits of themselves back and forth, mutually responding each to the other.

<Snip>

This is very similar to how people unite themselves and give each other parts of themselves — inner parts, mental not bodily parts—when they talk and listen.

Two amoebas having sex, or two people talking, form a community of two. People are also able to form communities of many, through sending and receiving bits of ourselves and others back and forth continually — through, in other words, talking and listening. Talking and listening are ultimately the same thing.

And finally,

When you speak a word to a listener, the speaking is an act. And it is a mutual act: the listener’s listening enables the speaker’s speaking. It is a shared event, intersubjective: the listener and speaker entrain with each other. Both the amoebas are equally responsible, equally physically, immediately involved in sharing bits of themselves.

My work is meaningful to me because it brings me closer to people.

I am a better person for having spent so many hours being bad at interviewing, awkward at asking questions, being self-obsessed in analysis.

It has changed me.

And, for the past five years at least, I have been trying to build a business based on this love of face-to-face research.

The past couple weeks have been a rollercoaster. Relief at such a clear signal that work, as I have known it, is over – and despair at ever finding work again.

But also, excitement at the prospect of surrendering to something truly different.

So I am not going to hold on.

To quote Edith, in the chapter on Communitas and disaster:

“We seem to be born for just such emergencies. We can see an openingbeyond; we make a kind of jump into hope, into the future, such as occurs in the now-generally accepted near death experience. We were born for this hope.”

PART THREE. There is no Initiation Without Inversion

April 16, 2020

The first phase of a rite of passage is separation.

Separation makes the great inversion of the social order possible.

We have been separated for a month, and there is a sense that this is just the beginning.

I weep for my 4-year old daughter.

Isolated from her peers, without a child in sight.

A world of children traumatized by benevolent isolation and a sociable distance.

Where is Communitas?

In “The Ritual Process,” Turner describes the rites of initiation for the Kanongesha (Chief) of the Ndemba in Zambia.

In a small hut outside of the village, the chief and his wife are disrobed, placed in a shameful posture as others “speak evil or insulting words against him”; we might call this rite “The Reviling of the Chief Elect.”

“It is rather a matter of giving recognition to an essential and generic human bond, without which there could be no society. Liminality implies that the high could not be high unless the low existed, and he who is high must experinece what it is like to be low.”

This inversion of status is the defining characteristic of liminality.

"The attributes of liminality are necessarily ambiguous....Liminal entities are neither here nor there, they are betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom, convention and ceremonial.”

And:

”In liminality, the underling becomes the uppermost.”

I was asked, “How does it feel to have your work deemed as inessential?”

I laughed.

Over the past couple weeks, the number of articles that seemed to announce this great inversion piled on top of each other.

My favorite example is from The Business of Fashion: “To Survive, Luxury Fashion Must Hibernate (paywall):

“Companies should reduce their cost perimeters, keeping as many of their personnel and key assets as possible, while stopping virtually all manufacturing and sourcing.”

And, The Atlantic, “Celebrities Have Never Been Less Entertaining:”

For now, Hollywood’s elite personas have isolated in spacious and well-stocked estates from which they are posting videos attempting to cheer up the masses. It’s interesting, if not always reassuring, to see these folks ply their crafts unmediated, without the screenwriters and film editors and cinematographers who typically help shape their images. Millions are tuning in. But often what they are finding is no more remarkable than whatever is happening in the viewer’s own living room.

Meanwhile, Eve Peyser quotes Madonna in “Celebrities Need to Read the Room Right Now:”

“What’s terrible about [coronavirus] is that it’s made us equal,” the pop icon said in a now-deleted Instagram video, where she is naked, soaking in a bathtub straight out of a romance novel. “What’s wonderful about it is that it’s made us all equal in many ways.”

WIRED, “Could the Coronavirus Kill Influencer Culture?”

Even if they walk the tightrope of compassion and inspiration, realism and “realness,” successfully, how can influencers truly differentiate themselves these days? Everyone is baking bread, everyone’s cat-cowing in their living rooms and everyone—if they have the time and means, of course—is turning to candles, baths, and cuddling.

It all makes me very curious to know how LVMH got it so right, so soon.

The mythologist Martin Shaw, begins his piece “Is this an initiation?” this way:

“I keep getting asked if the coronavirus pandemic qualifies as an initiation or not. I think so. When people start dying, that’s what we are into.

But—whether we grow wise from it is quite another matter.

And we can’t stretch out the comparison to a tribal or village ceremony too far. Because it’s not something curated by deeply prepared human beings, but by the earth. Much wilder, even more uncertain.”

And later,

“But is a war not an initiation for a soldier? Is profound heartbreak not an initiation for a lover? “

Standing in a parking lot behind the courthouse and across from a church.

My daughter and partner are circling me on bikes. The sky is blue. Clouds are white and round.

The steeple of the church throws its shadow across the roof of the church.

Everything is still.

“It was so windy earlier, “ I say to my partner as she passes. I am surprised.

“It’s windy now!”

The trees shake into motion, and I doubt the previous stillness.