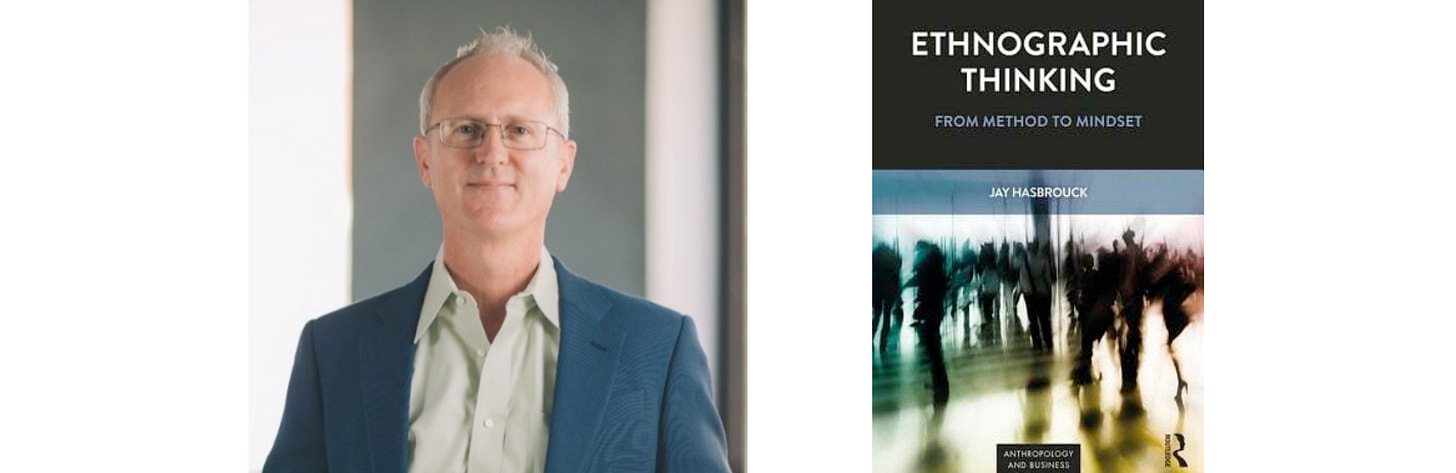

Jay Hasbrouck is a senior staff researcher on the ads team at Google, previously holding Pathfinder roles at both Google and Meta. He's the author of "Ethnographic Thinking: From Method to Mindset.” He specializes in applying ethnographic methods to drive innovation and strategic direction for companies, non-profits, and government agencies. His work bridges academic anthropology with practical business applications. He writes wonderful essays you can find at his newsletter Ethnographic Mind, including this on ethnography and collaboration, “High Intensity.”

Yeah, definitely. I think you may know this, but I start all these conversations with this question that I borrowed from a friend of mine who helps people tell their story. And I love it so much because it's so big, but because it's so big, I kind of over explain it. So before I ask, you're in absolute control and you can answer and not answer any way that you want to. Where do you come from?

Yeah, I love the question. And I think it's definitely, you know, a true researcher's question, you know, I think in a lot of ways. And I think for me, I think probably one of my most, you know, the biggest influences I want to say from being, you know, not just geographically, but as a person.

But anyway, I'll start with geography. For me, I grew up in Florida and very much a child of the 70s, I think, in a lot of ways. And I look back and only in hindsight have realized that I was definitely part of a few experimental education initiatives when I was a kid.

One of them called High Intensity, which was just like throwing a bunch of kids together to do creative things and come up with different experiments and execute on them and then think about what you did. And a lot of other programs like that. And I actually kind of admire what they were trying to do there in hindsight.

And I think from that, combined with my parents in a lot of ways were very free thinking and really encouraged me to think through things and pursue my own interests shaped a lot of how I approach what I do today. So I'm super grateful for both those things. And I think it's both a sort of a blessing and a curse in some ways, because it's sort of like, you know, I tend to run toward open-ended thinking.

And so sometimes it takes a little bit of effort to bring myself back, to reel myself back in from time to time. But anyway, I think that definitely shape a lot of who I am today based somewhere.

Yeah, you mentioned being a child of the 70s. What does that mean for you to be a child of the 70s?

I think it's a pretty unique time. It's like, you know, post 1968, and I think there was a lot of, you know, there was a lot of rethinking of what norms meant in the United States. And we were definitely part of a generation that was free range, for sure, like, so we were just out and about doing our own thing with not only, I mean, with, I would say, loose boundaries.

Like, the program that I mentioned, actually, the High Intensity Program is a great example, because there's a bunch of kids put together, given very loose assignments, and then we literally would scatter across the campus of the school and just go investigate or find out or make a little movie or record a video, record a video show or something like this. And it was pretty, I think, pretty exemplary of what was going on at the time. It's like, you know, like a free range, I think, in a lot of ways, a lot of rethinking and pretty open mindset, I would say.

Do you have a recollection of what you wanted to be, a young Jay, what you wanted to be when you grew up?

I don't really know. I mean, like, I think, I know that once I got to high school, I started testing, you know, you do all those evaluations. And I always scored highly on, like, analytics, right?

So I knew I'd probably do something around analysis, something that involved analysis, but I don't know that I would ever have identified anthropologists, right? I probably knew very little. I know I knew very little in high school about anthropology, which is a shame, actually. I think that should change.

Tell me a little bit about where you are now and the work that you do.

Sure. Yeah. Now I'm at Google. I've been here for over two years now and focus it primarily. I sit currently within the ads or primarily focused on the web. And thinking about what is the future of the web. And Google cares about this because they care about publishers, people who actually create content for the web, because that's where ads end up, right? But we're really seeing a lot of change. It's a very, very dynamic space right now.

And I'm sure you know this, Peter, just from your own experience. But there's a lot of changing. AI is just one piece of what's happening in this landscape where publishers are tending to use tools to think differently about their audiences.

It isn't all just about replacing writing, right? There are a lot of different backing tools that are making a difference in the lives of publishers. And in addition to that, the landscape is changing just in terms of what does media mean, right?

We're seeing a lot of shift in terms of how people are defining what does mainstream media mean versus what does alternative media mean. All of that's shifting. And so we're trying to get our heads around what does that mean for Google and how it is that we can encourage a high quality experience for users so that it doesn't become littered with poor experiences. And people are getting the kind of content that they want, that they're seeking.

What do you love about the work? Where's the joy in it for you?

I really love the, I mean, I've been reading a lot lately about trying to get at least more experience and more knowledge around complex systems and different models that people have used. I mean, a lot of that is, you know, early, early days, it's like things like cybernetics, Gregory Bateson, and those folks that were thinking about, you know, early on, what do systems mean? And they were using ecology largely as a model.

But trying to get my head around that is really exciting to me and thinking about, you know, interdependencies of these different systems that are in play. You know, the open web is a really complex set of different players and different systems and people. So that is very exciting to me, making sense of that and figuring out, you know, where to play in that space.

And also, I've been doing a lot more foresight's work, thinking about what are the trajectories that we see in this space and where do we think there are, you know, what's the range of probable, possible, implausible? And where should we be among those three? Where do we want to be?

When did you discover you could make a living? You're an anthropologist, yes? Like, when did you discover you could make a living? When did you discover anthropology as a path or something you might make a living in?

I was drawn to anthropology just as a passion, really. Like, I had a great undergraduate professor, her name was Judith Modell, at Carnegie Mellon as an undergrad. And she was awesome.

And I took a number of classes with her, starting out with visual anthropology and then moving on to cultural anthropology. And I was really inspired a lot by how she shaped, you know, how anthropology shaped how you think about the world. But then I was sort of like, well, I mean, there was no major at the time in anthropology at CMU.

So I ended up making, yeah, not for undergrads. So then I moved on a little bit, did some work for a while in D.C. in environmental policy, and then decided that, like, I was still drawing anthropology at CMU. So I went back to grad school just because, like, I knew that's the thing that really moved me and, like, engaged me.

So I had no idea what I was going to do with it. And then that turned into 10 years of undergrad, which is actually average for a PhD in anthropology, about 10 years. Is that right?

Yeah. And then I wasn't sure. I didn't go right into the applied setting right away. I did some teaching at CalArts for a while, which I loved, actually. It was a good experience. And then found out just by accident about a position at Intel. And they were looking for, they already had anthropologists that were on board there. And they were looking for someone to join the team. And I was like, wow, I had no idea that they would even care about anthropology.

So I joined Genevieve Bell's team there on the Digital Home Group. And that was a fantastic experience. And it was, like, I learned a lot about, you know, what are the insights that translate well in the applied setting?

Where do we get traction? Also, how to make use of theory in a way that doesn't feel alienating to your peers, right? So a lot of what anthropology has to say comes out of theory and comes out of a well-informed perspective of that. But it needs to be framed in a way that doesn't sound esoteric.

You write a lot about, I think, the politics, I guess, about making ideas and insights accessible, right? I feel like that's a thread that I see in your writing.

For sure. Yeah, I think one of the things that I like to carry with me that tends to work is, like, as you, first of all, as you walk into any room in an applied research setting, you know, the first time in that day they're going to think about research, and maybe the last time in that day. So, you know, that's not part of their daily routine.

And so often I'm thinking through, like, what is the question, the primary question that's sort of floating over the head of each person in that room, right? So often with an engineer, it's like, what are we going to make? You know, like, so they are thinking through everything you're saying with that lens.

You know, oftentimes a product manager will be thinking about when. When is this going to get done, and what is the timeline, and how can we push it forward, and things like that. And, you know, we as researchers, we're thinking why often.

Why are these behaviors happening, and, you know, what is the significance of designers, you know? So anyway, each of these designers are, I think, offering thinking, who are we designing for?

Oh, yeah.

So I think that goes a long way to just, you know, get myself, and I think for other researchers, too, to get ourselves out of that sort of like assumption that everyone is seeing it the same way, because they're often not.

In the role of the researcher, I mean, I feel like you, I mean, how would you describe how that has changed? The role of the researcher in an organization - how do you think about where the researcher sits and how the rest of the organization understands them?

Yeah, totally. I think that it's changed actually quite recently. Over the past five years, I've seen quite a big change. I think initially, you know, there were sort of two tracks primarily within large organizations, and I'm talking about the private sector here.

One of them being primarily sort of like validation and disproving hypotheses or proving hypotheses, sort of playing out what's already been and what's already in the making. And the other being the broader lens, sort of like, you know, what is, you know, how can we understand this market better? How do we understand how behaviors and attitudinal changes are shifting so that we can put our product in the right place? And you come and the researcher goes out, finds these things, comes back and reports what they found, right?

We were, I think in many ways, just the source of the answer. And I think in a lot of ways, what we're seeing is some change there. And part of that change is, in perhaps some ways, AI related as well. But part of that change is that in order for us to be truly collaborative, I think in many ways, it's helpful for us to think in terms of systems.

So it's not just us going out and coming back with answers, it's often how it is that we can be useful to frame questions for an organization. How we can tee up different lines of inquiry and how we can also take in the information that's coming from within the institution itself and the people and the knowledge they have and folding that into how we move forward with an initiative of any kind. So we've become the holding body and in many cases, we're defining the playing field, I think, much more often than we used to be. It's sort of like, help us find the right questions rather than help us find the answers.

Where have you seen that or what makes, where does that observation come from? It sounds beautiful.

I see it a lot in my daily work and I've seen it increasingly that the teams are, I think often in the past, maybe we're maturing as a discipline, I hope so. But I think a lot in the past, teams would get questions from different players, different stakeholders on their team. And you either, they were sort of thinking their only response was either answer the question or kick it to the curb because it doesn't make sense, right?

And I think it's a much more productive and I've seen increasingly researchers come to the table with like, well, yes, that makes sense. Let's put it in this context. Like the question you're asking is actually quite specific.

If we ask something one level up, we can answer five of these questions, right? If we use this method rather than a survey, if we use a panel for an expert panel, for example, just throwing that out, we might be actually, we might be able to answer much more and also expose new opportunities in the process. And so I think shaping some of that is, I think, much more valuable in terms of that conversation than being only reactive or off on our own in a bubble.

You, your book, Ethnographic Thinking, right, is second printing and is a beautiful piece. I'm just curious, tell me what inspired the writing of that book and how has it been received?

I think initially the first edition was really basically a work of passion. I was like, I feel like no one's saying this and I think I should say it, you know, like, and one of the things that really kind of goes back to what we were talking about earlier about what drew me to anthropology. And one of the things that did draw me is the way it changes how you think about the world.

So it's not really just like this method that, you know, it just gets leveraged and then spits out these results. It's really a change of disposition, I think, in a lot of ways and an increased appreciation for different ways of thinking and being in the world. And I think that's valuable beyond just being a toolset.

It's also valuable for helping an organization think about how it thinks about itself, right, or how it relates to the marketplace, its offerings relates to the marketplace. So it's very much a helpful vehicle for strategy. But no one was saying this at the time, right?

And so I think it was really just considered at the time when I wrote the first edition, the way that most people had intersected ethnography was as a tool for design. It was under design, right? Sort of like, okay, go out, find out what the users want, and then we'll make a thing.

And I really wanted to expand the conversation. So I put together an outline, you know, tossed it out there in the world and then got some interest. And lately, more recently rather, Rutledge was like, we'd like a second edition.

So I went back and tightened it up a little bit and added some more recent examples. I think it's doing well. I mean, people find it to be a nice – I think the intent was actually – the initial aim was to get folks to see ethnography in a broader way, right, in terms of its strategic value. But it also has turned out to be a good sort of primer for people who aren't familiar at all with ethnography just to get a sense of what it's about.

I'm trying to think. I have – so I came up in this weird brand consulting world where it was sort of ethnographic. Like, I don't – sometimes I very much feel like a fraud that I'm not academically trained as an anthropologist. I was learning doing brand audits and focus groups. And we did a lot of in-home contextual stuff. And I think I grew into ethnography professionally, just, you know, accidentally. And I'm just curious how you see traditional research, like how corporations sort of conventionally learn. I feel like it's just been upside down compared to how when I – you know, the world I came into was like they would – they'd do tons of validation. There's almost no cultural fluency. And there certainly aren't any anthropologists hanging around, at least in a lot of the client spaces that I started out in. But now it's wildly different. And I'm just curious how you think about traditional market research as usually performed by the corporation in America. And do you ever bump into it?

Yeah, oh, yeah, yeah. I mean, I think it's complementary in a lot of ways. I mean, as you know, like, in many ways, ethnography is a great starting point for understanding context and understanding – you know, getting that spark and understanding sort of where do we see – where do we see movement, where do we see new ideas. But also, there's a role for validation there as well.

But ultimately, if you want to talk scale, we need to come back to some of the quant that market researchers do and other folks too, psychologists, others that are out there really trying to say, you know, like, okay, so is what we're seeing here mapping to a broader trend? So I see them as complementary. I don't – I mean, I think at Google we have the market strategist. I think it's the role that would be that. And we work hand in hand with them, you know, to think about what's scaling, what's not. So, yeah, I don't see them as – but you're right. I think originally it was only that.

Yeah, yeah. And so I'm curious. I want to return – the stuff you're working on now sort of just dumbfounded me, honestly. You know what I mean? So the – what is – how do you explore or try to discover the future of the web is what you said, yes. So what kinds of – how do you get to work and explore that?

Yeah, yeah, we do. It's a combination of methods. A lot of what we do involves signal scanning, which is really just getting out there and into the world and seeing what's happening.

So that involves conferences, you know, who are the thought leaders in this space? Who are people who have – we think have vision? So it's attending conferences or, you know, looking at conference proceedings. Sometimes it's looking at patent filings. Like, what do we see growing as an interest area for people who are true inventors? You know, like, what do we – do we see a pattern there?

You know, sometimes it really comes down to, like, you know, trying to understand what's happening in, like, deep into, like, Reddit groups. You know, like, okay, what are they talking about? And then this is, I think, where the complex system stuff comes back into play. It's, like, making sense of all that. They're very – and this is not new to anybody who's done ethnography or anthropology. It's, like, really, really disparate sets of data, right? It could be visuals. It could be interviews. But it could also be artifacts.

And it could be, you know, patent documents, right? So any of this is, like, valid in identifying the patterns across them. So that's a lot of what happens at that sort of – on the foresight side of what I've been doing, trying to understand, you know, where do we think we start to see – we're starting to see what I call trajectories or movements in a direction that show distinct patterns.

Yeah. You had – you were at IDEO for a little bit. You were – just to return to the ethnographic thinking book, like, that for a long time ethnography really was sort of trapped in the design world as a tool. And I guess we've covered that a little bit already. But I'm just curious more about how you – where you'd say we are now.

Well, I do think that that has changed quite a bit. I mean, when I think about just sort of UX, if you take the subfield of UX, I think there's increased appreciation for the dynamic between design and research, right? And so it doesn't feel like – I think you're right. Originally it was – research was subsumed under design. It was like a tool within sort of in that – and the sort of supposition was like, you know, design thinking solves it all, right? It wasn't – it's like anything can get solved with design thinking, which is not what I'm saying with ethnographic thinking at all.

But I think that because of that was seen as – for a long time seen as the umbrella under which anything could get solved or addressed, there was a tension there for sure. Now I don't see as much of that, definitely. I think there's an increased understanding that, you know, like – and in fact, I see a lot more designers thinking in a research way and a lot of researchers thinking in a designing way. So it's like – I think the blurring between the two is pretty common now.

Yeah, that's interesting because I feel like there was a moment where it was like lean startup. It was just like everything was a prototype and it was all very – it felt very behaviorist in a way. And it seemed like it had scraped off all the interesting stuff off the top and kind of made everything into this exercise in behaviorism.

Yeah.

Well, I mean – You were – I was sort of frustrated. It felt like – yeah, but it's – I'm happy that we're not there anymore. But I guess where are we now in the – like, what's the best – how do you – is there an ideological difference? Like, how do you approach learning effectively?

Yeah, I think there's more of a conversation now. I mean, with Lean and Agile both – which both make me gag.

Is that right? I'm not alone then. I've never encountered them in person. I just – I've read about them and I don't quite understand them. I feel – it doesn't really make any sense to me.

Well, I mean, it's really about privileging the system itself, right? And there's very little room for conversation and for – and, like, as I was saying earlier, I think some of the value that we bring to the table now often is centered around framing questions, you know, like helping the whole group understand sort of what it is that – where do we – what do we want to learn? What are our learning priorities, right? And that's something that many organizations didn't – wasn't even – wouldn't even cross their minds, right? It was much more cut and dry.

And I think with Lean and Agile, there's no room for that. It's the – you follow the steps, you know, like – so I'm seeing a lot more room for people in the research space, particularly, to really get – you know, to take on that role and to help teams have these conversations around, like, is this a question that we need to understand where we need to – an issue we need to understand where we need to open up and think about broad questions? Or are we at a point where we're in the process where we need to drill down? And all of that shapes the kinds of methods that we would use and the kinds of – and the lines of inquiry that we would engage

So I think that I see that becoming much more collaborative. And maybe that has something to do with, you know, like, I do think in a lot of really big organizations that design thinking was like a really big trend. And then everyone was like, wait a second. This isn't solving everything. It may not be the right tool. So I think there's a little bit of a backing up going on in a lot of big companies.

Do you have feelings about MVP? And it's the – there was a post recently of sort of this tension between generative research and the beginning of a start-up versus sort of MVP and sort of MVPs being the sort of the – I mean, it's the same conversation, I think. But do you have an opinion on the appropriate use of prototyping versus generative research?

Yeah, I mean, when I was at Meta, the last team I was on there was called New Product Experimentation. It was really cool, basically like an incubator that sat within Meta. And there were, I think, 14 teams within the group.And they would – they each basically were a mini start-up. And they would – they were getting out there in the world and trying to develop some new – usually they were apps. Apps that help people come together around community or apps that help people build relationships.

Or usually they had something – they were related in some way to social media, but not always. And one of the things that they were doing was experimenting. And I sat on the central team, which was to help accelerate in whatever way possible with greater understanding for the kinds of things they were trying to build. So I would help them understand things like collective achievement as a concept. What does that mean? How can I help them build on those kinds of behaviors?

Another one was authentic expression. How can they help facilitate users who can – activities where they could express themselves authentically? And so while they were building those MVPs, they were also – they had the advantage of getting some of this insight about human behavior.

But then also each of them often would get a researcher on their team as well to sort of connect those dots, right? Like are we seeing people come together to achieve goals, you know, like with your version of that in your app, you know? So I think there's still – I think there is quite a bit of value within it – value for an MVP.

But I think it's – it isn't as sort of like Wild West as people, I think, assume. Like, you know, throw five things out there and just like – because I think the risk there is that if you adapt too radically, you overcorrect in another direction because something's not working, or you kill five features where there could have been two things in there that were actually quite useful. They just hadn't matured.

So we were in a good position there to help inform that, you know, to inform the process and help build from, you know, back to what I was saying earlier, sort of leverage some of the theory in a lot of ways around – that comes from social science. So I'd say it's a mix. Yeah.

I have sort of deep – I think it's theory envy or academic envy, having not gone to – not having studied it. But how do you tell me – can you just tell me a little bit more about how you incorporate the theory into the work? And if there's a practice around that, or is it just because you've studied it, it's in your – you carry it with you. And so it gets applied, just to be as explicit as possible about this because I want to copy it.

I think – well, I mean, maybe, you know, I might be at a slight advantage just because I've – you know, like, I was put through the ringer in grad school, but it's not something that PhDs alone do. You know, I think that a lot of people are doing this, and there's certainly no reason to not do it. One example.

In that same group, in New Product Experimentation, one of the things that we were really interested in learning more about is, like, how does a community come together? What forms deep bonds between people? And so what I – and I just, you know, sort of referred back to what I knew about how it is that people come together.

And a lot – and some of that in anthropology focuses on what we call rites of passage, which is – I mean, a lot of people know about what rites of passage is. It's from an anthropologist's fang in death. And one of the things that he forwards is this theory of how it is that people form deep bonds, and it comes from a serious – this sort of cycle of separation and then sort of meeting some challenges, overcoming those challenges together, and then coming out of that experience with a new layer of identity.

So that's a really big oversimplification of what it is that he is not invited to rites of passage. But so what I did is I took that model and I helped simplify it and also translate it to the tech setting, right, in terms of apps and people interacting with one another there, and help them use that almost like a checklist. Like, are we helping people – you know, are we helping people feel like they're part of a special club or whatever?

The separation part, right? Are we helping them overcome an obstacle in some way, right, in their lives that they can actually feel like they formed a bond together? They suffered together and now they're coming out the other side, right? And then are we helping them express this new connection in some way? Are we helping them form a new layer of identity on the back end of this cycle?

And really just sort of walk through that with the team so that they can think about not only just the features in their product, but also the order in which they occur and, you know, how it is that people are invited in and ushered through the experiences that they have there. So I think that's one example where it's a theory, but it's not – you don't go to the team saying, I've got a theory for you.

Yeah, I'm curious. Are there particular touchstones that you keep returning to from the universe of theory?

A good example to your point, Peter, about – I mean, that was tapping anthropology specifically, right? So something that I did learn in grad school. But another project that I worked on focused specifically around storytelling.

And that was something that I – you know, storytelling is certainly part of anthropology. It's part of how we learn as anthropologists and also in many ways how we convey our insights through stories. And Margaret Mead has this great quote that we learned through metaphor, that we learned through stories and shared through metaphor. And I think it's very true, but I did not have any sort of formal training in storytelling. And it's a practice that's – you know, there's a long tradition in that practice. And I think maybe if you were an English lit major, you might have received some of this in your training, but I didn't.

And so I did a lot of secondary research around storytelling and borrowed a lot from human development studies, which was how do kids learn to tell stories? So there's a very well documented process that takes place where kids start out with just sort of fragments of ideas that they pull together. And then they – and I'm forgetting the terminology, but they slowly build up to an actual narrative, what they call primitive narrative, which is like there's probably no ending that makes sense out on its own.

But if you knew the context, you could string it together yourself as a listener and then write on up into a full actual story, right? With beginning, middle, end, a central character and all that. And I use that a lot because it was really useful to think through, like, all of us has this embedded, these different stages embedded within us.

Like, we're also – and sometimes with your friends, you might tell a primitive narrative because you know they're going to get the Ponsulani you don't have to see. You don't have to say it, right? And they're – sometimes we're just making associations between ideas, for example.

And it's not even – I'll have to think about what the terminology – the term is for that. But in any case, each of these could have and could have corresponding uses in terms of enabling people to tell stories, right? So maybe not everybody wants to tell a full story.

Let's say on social media, for example, you may not want to tell a full story. You might just want to share the basics with your friend's circle. And that's enough. It's enough to connect with people around a few ideas. And that's your – that was your objective anyway. So it's not, you know, it's not a full – you're not writing a movie or a script or something, but you are trying to – you're trying to share and connect.

That's beautiful.

And so those tools, yeah, exactly. So we've all got these little pieces of how it is to tell a story. We tap on different stages of them for – in our lives.

I feel like I learned way too late in life as a researcher that I think in early career I felt like I was supposed to go out, find something, and then report it. And they would just take it – it was just information, really. And then maybe maturity taught me that I was most compelling when I was just telling a story about the research in a way. And then smuggling in all this insight that I didn't even know that – but I learned that really late. Even after years of, I think, industry people saying, storytelling is a skill. Storytelling is a skill. I didn't really know what they were talking about. And so, yeah, it just – I just watched one time telling a client a story. And I just saw, like, a whole giant light bulb go on and realize that that's what's happening.

There's a ton of cool research in neuroscience as well around emotional connection with stories and the ways in which, as you tell a story, and you start to convey different senses, like sense of smell or sense of sight or sense of taste, et cetera, that it actually fires up some of the same neurons in the listener's mind. So there's a lot of different tools like that in storytelling that go a long way. And people connect on the emotional level first, right?

Yes. Do you have a preferred way of – like, how do you learn? I mean, just listening to you talk right now, I realize I've – you know, I learn through people really well. Like, I'm a good – I like talking to people. I like getting into conversations. Do you have a particular way of learning that you've learned or that you prefer?

Yeah, I think I learn visually, really. That's appealing to me. But also, obviously, through conversation as well and through storytelling, for sure. Actually, I think I learn a lot. And I think what really stimulates a lot of my thinking is things like movies and actual narratives that really start to trigger questions, I think, in a lot of ways, about what are the tropes we're all sharing and why are we sharing them and what – you know, science fiction is a great example. The stories we're telling ourselves, I should say, are a great way for me to learn.

But I think all of the above in that sense. And, you know, I think, for me, reading, for sure, but it needs to be, like, pretty purposeful. So it's like, yeah, I'm very intentional about what I'm reading. But I actually wanted to share with you this book that I have sitting on my desk by chance. It's called Do Story by Bobette Buster. It's a really short read, but she goes through some different, I think, principles for storytelling that I think a lot of people would find useful as researchers, but just anyone. I highly recommend that.

Cool. Thank you for that. So you've worked in so many different contexts. Is there anything that you haven't studied that you sort of would really love to explore?

I don't know. I mean, I think I haven't done a ton of hardware work, which I think would be interesting. I mean, at Intel, we did the guts for the hardware. But I think that the timelines are different in that industry. So I think that would be an interesting place to play. There's a lot of interesting stuff going on in transportation and mobility right now.

I mean, obviously with automated driving, it's a crazy field right now. So that would be interesting. There's no time to do it all. But I mean, those things, in terms of what I read in the news, if I see something around that, I am drawn toward it. I'm also, I really find fascinating what's happening in sort of the space industry. What edges are we pushing there?

You think about just the industry itself and how fast it's growing and how much more capable we are. I mean, I think just satellites alone are going to change our lives a lot within the next five years, just the capabilities and the scale.

What are you thinking about? This is news to me.

Well, I mean, one example, of course, is SpaceX. Elon Musk's effort there where he's trying to, well, he is in many ways, launching satellite internet access. But you can imagine, well, that alone is huge, right?

If the globe suddenly has access without being wired to the internet, that changes a lot. It changes a lot for a lot of people. But beyond that, I think it's also thinking about what is the, how does it change our perspective?

What more might we do with a lot of things orbiting this earth? And if it becomes less and less expensive, just in terms of seeing what the planet is doing, thinking about that pair of AI, thinking about how it might impact the way we see weather patterns, the way we could actually become much better systems thinkers with this greater ability to see the world differently. So I think there's a lot of opportunity there that is just starting.

You mentioned a few times the systems thinking. I haven't spent a lot of time studying it, but you mentioned cybernetics. And also, being a child of the 70s, I feel like the cybernetics was very much a 70s.

In my mind, anyway, it feels like a 70s idea. You mentioned Bateson, right? Can you tell me a little bit about the influence of systems thinking? What does it mean to you to be thinking at that level?

I think one of the cool things about cybernetics and some of that early thinking was this ability to start mapping concepts from different disciplines and thinking about how we can learn from that. So thinking about the way that we produce technology or anything in our lives as humans in ecological terms, right? So thinking about interdependencies, thinking about the impacts and externalities of different actions, all of that was pretty new at the time.

And so it's really helpful for us to start thinking not just in linear terms, but in terms of consequences and in terms of how these systems interrelate. I'm just scratching the surface. There's a whole field of complexity studies that I'm just starting to, you know, I've got a stack of books that I need to dig into.

But there's... What's the attraction? What are you doing when you're diving into complexity science?

I think for me, I definitely am a puzzle solver as a person. I think it feels like a puzzle to me in a lot of ways, and I really like... I just bought a model of the Roman Colosseum, and I'm putting that together now because I just like to do that Oh, that's awesome. But I think for me, it's very much that, like, how are the pieces coming together? If I pull this, what happens over there? Or what multiple things happen as a result of this one change? And that's, you know, it fits well, I think, to the world of technology in a lot of ways, too. I mean, understanding those complex systems and the relationships between humans and technology. So I think, yeah, there's a lot that I still need to learn in that space, but that's the draw, primarily. Yeah.

I'm curious, like, we've got a little bit of time left, but you've spent so much time at that space where, you know, humans and technology meet. Like, what have you learned in that space? Like, I spent a lot of time talking to people about, you know, consumer goods, you know what I mean?

Like, rice and tea, and you talked about hard versus soft earlier, hardware. And I'm just curious, what have you... What do you understand or sense, having spent that much time talking to people or understanding that relationship that somebody that hasn't doesn't?

Yeah. That's a good question. I think there's a long tradition, certainly, in the sort of Western larger narrative around this tension between fear of technology and technology as a, you know, liberating tool, right? And they're both sort of always there. And it's interesting that the way we bounce back and forth between them, I think I've learned that quite a bit. I mean, when I was at Intel, we occasionally used to get invited to these, like, future of, you know, like, initiatives. So we'd go to, like, the kitchen of the future, right, that some other company would... And so we'd have to go do this. It was interesting in a lot of ways, but it was so far removed from people's daily lives, right?

Which makes sense because it was imagining in reality, but it was definitely not the way people... It didn't reflect the priorities that we saw in the field in terms of how people manage a kitchen, for example, right? Like, how many people need, you know, a computer and their refrigerator?

Probably none. So I think there's, you know, a lot of that made me, you know, sort of think about, you know, what's necessary, of course, but also this tension between some of the fear and some of the more utopian approaches. So the Silicon Valley is filled with, like, lots of techno utopian, speaking of the 70s, right?

It's like, techno utopian, like, it will solve it all. We'll get there through technology. And you see, in many cases, you know, the public, they're not riding that same train.

And so we really think carefully about what does that tension look like there. You know, another example there is one of the projects we worked on focusing on green home, green technology, basically. Thinking about how to help people better manage energy and different resources within the home.

And the original sort of original drafts of some of this thinking with our chip architects and our engineers was, oh, every house needs a mainframe. They need a server in their house that will track all of the things and all of the electricity usage and everything. In the future, everyone will just have, like, a computer that is, like, the brain of their house.

So we went out and we were like, okay, well, who are the people we need to talk to that are at the edge here? Who are people who are already thinking a lot about technology in the home and they're ahead of the game, right? And we spent months talking to people in different climates and everything.

And one of the primary learnings that we had was they don't want the server and that they don't need to centralize anything. And in fact, what they're much more drawn to is sort of disparate systems that they put together themselves in different ways. One was for just controlling temperature and they're fine with that.

And one was for understanding water consumption and how much water they're saving with their water reclamation system. And because they want to make sure they know they're updating as needed and using when needed. And I think in large part that came to fruition.

Like, you don't really see people with servers in their homes. You see them with Nest thermostats. You see them with their phone. You see them with Siri, all these different subsystems that they're using to manage how they're living. So I think the Utopian vision, it's easy for like technologists to get carried away with it, but I think often how it plays out in the real world is like in smaller scale, incremental ways where people find the right tool for the right place in the right time.

I remember, I never know how to attribute it, but I feel like some, I feel like a quote, and I'm just going to say it and you can respond to it. But it was the effect that the first casualty of technology is ritual.

Is that I have not heard that, but I think maybe. Yeah, I mean, you could also imagine rituals coming out of technology to new rituals emerging from technology.

That's what I was thinking of in that story. You told that people were somehow they were preserving all these little rituals, perhaps, or these opportunities of anyway.

One of the metaphors that one of the participants offered in that study was like they said, like living on a ship, and that's how they thought about their house, like different gauges and different tools that were used for navigating or for protecting themselves. I thought that was a great way to put it.

How do you use metaphors in your work?

I mean, I use them all the time. Any chance I get, actually, I'm using a metaphor. Let's see, I mean, for the current work that I'm doing, one of the things we're trying to convey and also share is some of the shifts that are happening in the web and trying to share the disposition of publishers out there in the world.

So really trying to think through what's the mindset of a web publisher who's facing all of this. So in that case, I don't know that I have a solid, I'm still in the mid project here on this one, but definitely a better example is probably the one I just shared, like living on a ship, things like that, where you've got folks where you're trying to help share not just what they're doing, but what is the approach they're taking? What are some of the rationale?What is the larger view of the world that's embedded into the systems that they make?

I think with publishers, we're still trying to iron that out. I mean, with web publishers, because it's really, really changing a lot every day. So maybe struggle is at the center of that metaphor.

Cool. Well, listen, Jay, thank you so much. It was a pleasure to finally connect face-to-face after sort of interacting and knowing each other in that LinkedIn way for many, many years.

Likewise. Likewise. It was a pleasure to chat and get to know you better as well. And I look forward to connecting in the future.

Yeah, cool. Awesome.

Share this post