John Bowe is a speech and presentation consultant, and author of I Have Something to Say. He specializing in corporate and individual presentations. John contributes regularly to CNBC about public speaking. He has written for The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, GQ, McSweeney’s, This American Life, and is the author of numerous books. His work has been featured in the Harvard Business Review, The New York Times, and he has appeared on CNN, The Daily Show, with Jon Stewart, the BBC, and many others. He lives in New York City.

So in this conversation series, I start all my questions, all my interviews with the same question, which I'm excited to ask you. Because I love this question. I borrowed it from a friend of mine. She works up here. She does oral history. I know you have a history with oral history. And it's a big, beautiful question. And so I over-explain it. So before I ask it, I want you to know that you're in total control. You can answer or not answer any way that you want to. All right. And the question is, where do you come from?

So part of me wants to do this in the most literal way possible. Grounded way imaginable, and part of me wants to just go way big. I think I come from the most disastrous, panicked, spiritually aggressive place possible. Which is, we're all doomed, and I have to come in and save everybody and think of some great solution that will save the world. So that's where I come from on one level. On the other level, I come from Wayzata, Minnesota, which is 12 miles west of Minneapolis.

And what was it like growing up in Wayzata? Is that how you say that? Wayzata.

I heard something that said it was the third richest suburb in America at that time. And that was America's richest time. So I grew up in the heart of white privilege and bloated 70s America at its apotheosis. And it was a disaster. We weren't among the super, super wealthy, but the town that we lived in was not facing a lot of crises. And it was like that documentary, if you've ever seen it, called An American Family about the seventies family that's just falling apart. Everybody's alienated, the parents are getting divorced. One of them might be cheating on the other one. They just have three cars and one of the kids is coming out. Another kid is maybe on drugs. I can't remember. Just everybody's going in their own direction and nobody is pulling together. There's no sense of family unity culture. It's all just that moment when American culture is just falling apart because there's too much excess and nothing sustaining people, no kind of binding myths or anything. And so that's where we came from. Just, there was no - we had all the freedom in the world. We all had our own bedroom and somehow it was a disaster.

And that feeling you described that you come from this place of "World's on fire. I need to save it." Is that captured?

I know, I just - I'm growing up in like the richest society, the best most materially satisfied demographic in history, in the entire world. And yet, most of the time I thought that life is a problem. Oh my god, I can't believe this. What are we going to do? This is - How can we go on? How can we go on? And so like my family was completely not religious. And yet from a young age, I was almost like some Flannery O'Connor character. I was obsessed by whatever. I could even put a name on it, but it was God and religion and spirituality and something like that. There had to be something. And I guess that was nature, but I kept looking for other names or dimensions to it and there weren't any. We weren't going to Sunday school or anything like that where I could have gotten glimpses into the fact that, oh, people are putting a name on this. People have struggled with these same problems before. You're not weird. You don't have to feel ashamed or weird or isolated. Here's a whole trajectory that you could jump onto that would explain a lot of that or give you options for explaining it in the way that you want.

Yeah. Yeah. What kind of child were you? What, how did this express itself? What did it look like? John Bowe in Wayzata?

I think it was a bit of a wiseacre. I think it was a total rebel and not an interesting one. I thought I was interesting, but I don't think I was at all. Like our fifth grade teacher said his name was Mr. Haybison and me and my best friend, Mike, who was also a miscreant. We would say, okay, Earl. And then he'd say, write down my name, Mr. Haybison, 200 times. And we'd say, okay, Earl. So that was the level of rebellion that I thought was interesting. Or stealing vegetables from a church vegetable garden. Or dropping rocks off of a railroad bridge onto cars and thinking we were like Julian Assange or something.

Do you have recollections of what you wanted to be when you grew up?

Yes. I told my mom when I was about five or six years old that I wanted to start a new religion and then retire and be a farmer.

Wow. Wow.

Isn't that crazy? Isn't that totally? So then when I was about eight, I discovered writing. I was looking at a book that I wouldn't read. It was some book by a Norwegian writer named Piers something called The Dwarf. And it won. It was about a court jester, I think. Anyway, I was looking at the cover, which had this really mean, scary cover, and I said, I'm going to be a writer because writing will solve all the world's problems. And I have, again, no idea where this stuff was coming from other than just probably total desperation.

Yeah. What did it mean to you to be a writer?

That there was this magical thing you could do that didn't use materials, that you could wave it around like a magic wand and it would solve the world's problems. Or at least theoretically, potentially.

Tell me a little bit about where you are like right now and what you're doing now.

Short answer is I was a writer and a journalist forever. I did oral histories. I wrote for the New York Times magazine a lot and the New Yorker sometimes, just long nonfiction, high quality journalism. And eventually that led me by accident to discover public speaking and the idea that you can train people to speak in public and that it just unlocks all of these psychological pathways and ways to connect with people. So before that, I was not at all interested in public speaking. I thought it was corny and uncool. And then I realized, Oh God, this is like free or super, super cheap, fast psychiatry sessions and it helps people in the same exact way that I wanted to since I was a kid. Here's a way to use words to help people, but it's not what I thought. It's not me writing. It's me helping other people get access to the skill of expressing themselves. So it's cool. It's weird in that way that you always are wrong. And then you discover really what you were trying to do in a much better way. It's not what I thought at all. It's much cooler and easier than that.

Yeah. What is the joy in it for you?

Oh God. So imagine when you get a haircut or a new change of clothes and you look at yourself for a second, just that second where you think, Oh my God, I actually look okay. For me, when I can help someone express their ideas better or learn better than just doing it once is I can give them the skill of doing it every time. They become so empowered that they literally become happy. I can say that most of the people I work with become way happier. And this isn't after working for a hundred hours, it's after working for two or five or eight hours. So it's pretty, it's a pretty lucky job. It's a pretty great job.

Yeah. And how did you discover it? You're the, as a journalist all that time and I want to go back and ask you about some of that stuff too, but what was your first encounter with public speaking when you discovered that it was something that you could do?

In my own history, I was always a pretty mediocre public speaker. I didn't like it. It terrified me. I don't know if I was as terrified as a lot of people, but I was definitely terrified, and I never prepared for it in the right way, and so I was always pretty ineffective at it. And it troubled me a lot, because I couldn't figure out why I was bad at it. I have all the tools to be good at it. I'm expressive, I'm a goofball, I don't care if I look stupid. I know that I'm gonna look stupid sometimes, but I also know that I can be smart sometimes, so I just couldn't figure out why when I talked about a book or something that I had worked on for years, I couldn't speak about it in a very interesting or compelling way.

What would happen? I think anyone who heard me would have thought Oh, he seems like an amiable, okay guy. But that's it. Nothing more. You, no one would have walked away with any particularly clear, vivid message about the book or the thing that I had just worked on. And I didn't know this at the time, but I was really passionate about these projects, but I never knew how to talk about my passion. I would have been embarrassed by that idea. I'm passionate? No. I, so I, and I didn't know that when you talk to people, you're supposed to tell them what to think. Here's why I'm talking to you. Here's what I want you to know. Here's what I want you to believe. And so I would talk to people and just on a factual level, like the job of public speaking is for me to take the facts in my little hard drive in my brain and put it in your little brain, and that's it. We're not going to talk to each other like people or like people who have hearts. I'm not going to convey to you any of the moral or emotional reasons for me doing what I do, or any of your own, equal those capacities in you. And so I just thought it was purely intellectual and purely factual, and there's no other element going on when we speak in public. And all of that other stuff besides the intellectual stuff just annoyed me, and I thought I'm a writer, they should just read the damn book. Why am I here on the stage talking to people?

Yeah, I love how you described - you said you didn't know that you had to tell people what to think. There's a woman, her name is Fiona McNae, and she runs this, I probably shared this with you, a semiotics agency in the UK, and she has a TED Talk. And I always quote just the title of the TED Talk, because it's about semiotics and communication. But it's "Taking responsibility for being understood."

Oh, that's so great. Aristotle would love that. That's, yeah, I didn't know. How would I, how would people know what to think or how would people know why I'm talking unless I do the work of thinking beforehand? What do I want them to know? And I just passively thought that's all supposed to come out naturally and organically. And that's a nice thought, but it's just not true.

And you mentioned Aristotle. What - So you discovered public speaking. What did you do about it? Let's go. Let's go back.

That was my whole sort of past history with public speaking. I didn't know anything about it other than that it was a pain in the ass and a very uncool thing to learn about and people. I was too cool to learn about it. Maybe there were some uncool people in business who were so shy they had to learn about it, but that wasn't me or any of my supposedly articulate artistic friends. So then fast forward to 2009, I'm doing this oral history about love, and I interview my step cousin in very rural Iowa, Cousin Bill, who was a recluse. He was like a real textbook recluse who lived in his parents' basement. And his main job was to mow the lawn in the town square. He had knee socks, black knee socks, which he wore all year round. He had never kissed anyone, never gone on a date, never had friends, never hung out, never did anything. A totally nice guy, but a bit of a man child. And when he was 59 years old, he got married. And so my family in Minneapolis would always comment on that in sort of snarky ways and just wonder who he married and how in the world that had happened. So then when I became a big boy journalist, I could go approach people and ask them what's your story? What's your deal? So I did that with him. And among the questions, cause I wanted to know for this oral history about love, what is it like to have love if you just never had anything at all? And then you're living with someone and you're married and you're, you are in love. What does that mean? After 59 years of nothing.

And during that interview, I asked him, how did you talk to your future wife for the first time? And I assumed that his answer would involve psychiatry or therapy or meds or something, reorganizing the way that he thinks or reorganizing his brain chemicals, whatever. And he shocked me and he said, I joined Toastmasters.

So I knew Toastmasters is the world's largest organization devoted to teaching the art of public speaking. And it was started in 1924 by this guy named Ralph C. Smedley, who had worked for the YMCA developing education programs, classes and stuff. And he noticed at that time that millions of people were moving from these rural farm towns into cities because the farm economy was becoming mechanized. And so where that once employed 80 percent of the people in the U.S. suddenly now I think it employs 3 percent or 2%. And so all these people were coming into cities and they were shy. They were country people. They didn't know how to be fast, fast tongued. Lib, whatever. And he realized, Oh my God, these people can't get dates. They can't get promoted. They can't unlock their potential and their intellect and their capacities. So I'm going to teach them how to speak. And he did. And he went back to these Greek people and Roman people who originally taught public speaking and had really great techniques and theories about it. And he modernized it and he turned it into a club where people could go at their own speed and learn the rudiments of public speaking from each other at virtually no cost. So I just thought all of that was cool. It all aligned with everything I thought about, like capitalism and technology and modern society. And we're all falling apart. Everything since I was a kid, we're all doomed. We're all going to hell. And here's this really humanistic, super practical thing that this guy invented, where we can all teach each other how to connect and how to talk and how to function better.

What did you sense in it? You're saying it right now, but what was the attraction? You say yeah - what did you sense in Toastmasters that was so attractive?

It's not a corporate thing. It's not something anybody owns. It's not something that you have to pay a lot of money for. It's something you show up and here are your fellow citizens, rich, poor, whatever gender, race, whatever creed. And we all teach each other how to belong, how to participate. What's the thing you quoted from the semiotics? Taking responsibility for being understood. It was very much that. It's like a different way of expressing that. You go join, there's no credentialed expert who's teaching it. It's just this curriculum which is self, whatever, self-perpetuating. And it was just cool, you go, and the people there, no one's the boss. It's like AA for shy people. It's a church, but nobody's the president. Nobody's the boss. No one - I guess they can kick you out if you misbehave, but in general it's super democratic. It's everything that was the cool at the heart of the United States, which has become less accessible.

I had read Bowling Alone by Robert Putnam, which charts the decline of participation in groups. And so up until the 60s Americans participated in groups more than any other country, and that meant it could be bridge clubs, or religion, or political groups, or it could be the Ku Klux Klan, it could be the PTA, anything where people get together and share their beliefs, whether they're good or bad. And all of that had declined mostly thanks to TV, like everyone was now at their home watching TV. So this Toastmasters thing just captured my attention in a hundred different ways all at once. So that led me to want to write a book about it. And I traced the ideas from the founder of Toastmasters back to where he got them from ancient Greece and Rome. And I thought that was all really cool too. The Greeks invented democracy. I could put that in quotes because it wasn't really full-fledged democracy at that time. But anyway, once they invented democracy, the world went from a place where you were forbidden to speak to crowds to a place where you were suddenly required to speak to crowds.

Whoa, what do you mean? Can you unpack that a little bit?

Before the invention of democracy, only muckety-mucks could speak in public. Like big famous generals and stuff like that. Yeah. And the rulers of Greece were these sort of oligarchs who weren't really - their name wasn't public. They weren't like public politicians. You didn't know who they were necessarily. And so the generals were the most popular figures who represented power. But you yourself could not go on a street corner and start proclaiming your beliefs. And then suddenly with the invention of democracy, public participation kind of supplanted violence or whatever was the prime mover of civilization before that. And so almost immediately, whoever was a cool, good public speaker started amassing power. And they would have these forums where should we go invade Sparta? Or not, or should we raise taxes or not? And everyone was encouraged to speak up and contribute. And if you sucked at that, or you were reluctant to do it, people didn't trust you, didn't want to do business with you, didn't want to have you marry into their family. So suddenly it just became imperative to learn it.

Yeah, unbelievable. That's like a new technology, right?

Yeah. It's like a gold rush. Suddenly all of these philosophers and teachers rush into Athens and it's exactly like the internet and Silicon Valley or something. There are a million different theories for how to do it or techniques for how to do it and they start sort of hacking language. So think about it. If you don't know anything about this stuff, you think that when you talk to people it's almost like your hair growing. Your hair might be different than my hair, but you didn't do anything to make it grow that way. That's just you. So my speech is just - I don't control it. It's just this product that naturally comes out of me.

Yes.

So this moment where they start looking at speech is the first time where they shake their heads and they say, no, it's not. You can control that just as much as you control how you cook or how you dance. And so they start hacking into everything like introductions or why is a story better when it's broken into three parts or a joke? It's - what does rhythm have to do with logic? What does rhythm have to do with why one person is persuasive and another person seems weird? Why is poetry - if I vary my voice and I, instead of just talking along like this in a monotone, why does that make you trust me and like me and believe me more? And so they start studying this stuff. They start studying why is the past tense gonna - past tense is really good for blaming people. Future tense is really great for forging a solution. Peter, you didn't take out the garbage. You've always been a lazy jerk. You don't do this. You didn't do that. You know for the last three months you haven't done that. And you can just swing it on me and say John, what do you think would be a good way to go forward? John, I understand your concerns. What do you think is a fair way to divide the labor going forward? No, Peter, I'm talking about the last three months where you did blah, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. And politicians do this all the time, but in your own life, you're just shifting the tense, just shifting the tense. So you realize there are these really specific language hacks that people kind of use sometimes unconsciously. But if you become conscious of them and you study them and you use them like a - you'll win more arguments and become a more credible, empowered person, but also just, you'll know how to express yourself better. You'll get these tools.

And is this rhetoric?

So that's rhetoric. The fancier definition of rhetoric is the study of all available means of persuasion and so Aristotle's theories - whenever we talk to each other we're persuading each other of something. It might not be nefarious or whatever, but it's - I want you to listen to me. I don't want you to look at your phone or drift off or walk away from me while I'm talking to you. Or you know I want you to hire me or I want you to buy my product or fund my startup or whatever. And so if I talk like a weirdo, that's less likely to happen. If I talk persuasively in a way that engages you and gets you to buy in, then I'm more likely. So what are the things I can do? The many different levers I can adjust or whatever to make you do that, and what are the things that would stop you from doing that? So it's a study. It's not just like a study of communication or study of words. It's a study of all this kind of psychological, pre-psychological stuff that turns out to be super valuable and interesting.

How do you apply the lessons of rhetoric and Toastmasters in your - when people come to you?

Okay, so most people who come to me are pretty smart. I have very few dumb clients, and yet they don't talk like they're smart. Their love, their intellect and their sort of knowledge base is at a much higher level than their ability to use that or to present their ideas or get other people to buy into their ideas. And so I teach them these basics of rhetoric, these basics of speech training. The main thing I help people with is people, these days, we're so enamored of data and knowledge and facts that we tend to bombard each other with facts as if facts will win the argument or speak for themselves. And so the main thing I ended up doing for people is getting them to understand there's all the squishy softer connective tissue in communication that you need to get good at and you need to remember to use it. And then people will start listening to you and understanding you much better. You'll feel emotionally more connected and that's nice. You'll feel included, you'll feel respected, but also just people will get what you're talking about. You'll have a better chance of getting promoted at work or getting funded or whatever, selling your product.

I feel like this is like the constant battle between - I mean there's so many ways of expressing it, but - Have I shared with you, I'm just gonna - another one of my favorite references is Ursula Le Guin. She has an essay called "Listening is Telling." Do you know this one?

I've heard of her, that sounds interesting.

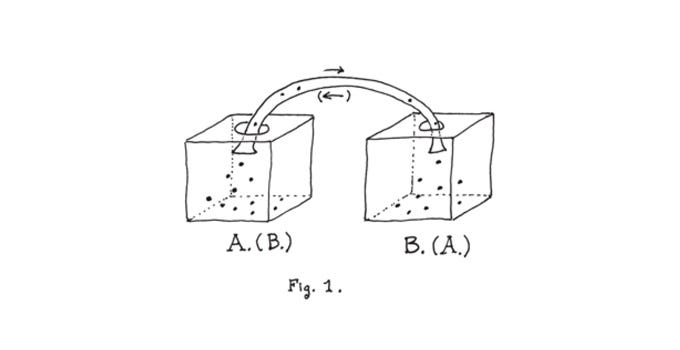

Oh, you'll love this. I'll send it to you if I've not shared it with you already. And she's got some diagrams in it in which she - she drew, she draws what you described before that we have this conventional understanding of how communication happens in which communication really is about the transmission of information. And so there's a - she has a diagram of two boxes with a tube connecting them, you know what I mean? And language is these bits of information. I'm the sender and I'm sending bits of information through language. Yeah. You're taking it into your little box and then we'll take - we'll switch positions. You'll be the sender and I'll be the receiver.

And she says that's ludicrous. Anybody that's actually been in a conversation knows that it's nothing like that. Conversation is - it's a reciprocal, it's an intersubjective - it's - there's all this crazy stuff happening, you get lost in it. And so a better diagram - she uses the metaphor for amoeba sex. Yeah. Is a better metaphor or analogy for what happens in communication - in conversation is you get lost. I think when amoebas have sex the boundaries - they become one in moments.

And so she uses that as this - I think she builds a whole framework about - around feminist communication around it in some of her novels. But in this essay in particular, she uses those diagrams. And I'm wondering, is that - does Aristotle and rhetoric - were they talking about amoeba sex?

Totally, absolutely. Totally different terminology, but yeah, totally the same idea. Aristotle has this thing, which is the thing you're going to learn in any public speaking class, or not public speaking, but rhetoric for sure. It's an old canon. First of all, whenever we talk to one another, we're trying to persuade each other of something. And second of all, when we do we use three different main tools. One is facts. The second is emotion, and that's do I get you to laugh, do I get you to cry, do I get you to feel sorry for me, or feel mad about yourself and your own plight. And then you're going to interpret my same set of facts in a very different way, depending on what emotion I arouse. And then the third thing is ethos, they call it, which is character, which has a really wide definition, but basically that means what you know about me on my resume, my education, my background and all that, but it's also how I perform my active communication. Am I together? Am I shy? Am I sexy? Do I have really amazing clothes? Do I talk down to you? Do I talk up to you? Do I talk fast? Am I super organized in my thoughts? Are the examples that I give to you examples that you understand because they're in your wheelhouse? So that's character. It's like the competence with which I explain my ideas. And he said of these three tools, facts, emotions, and character is by far the controlling factor in persuasion. And so I might be right, and I might have some great idea, but if I tell it to you in a way that sucks, or I'm really boring, and I just stick to the fact I'm being dumb because I'm not paying attention to what you - what really moves you.

So if I'm talking to you, you might be looking at my clothes, you might be looking at the fact that I've got curry on my shirt, you might be looking at the fact that I told you I'd talk to you for five minutes instead I talked for 40 minutes. You're looking at the whole of me, and I think you're just looking at my fact. Yes, so that's where it comes back to amoeba sex. It's definitely not like those two boxes exchanging messages about the fact. They're checking each other out sexually. They're checking each other on some Freudian level. Do I want to mate with you or kill you? Do I - am I impressed by you? Do I like you? Do I want to follow you? Am I worried about you liking me? All this other emotional stuff is in there besides just the simple factual level.

You describe the person coming to you as somebody who's super smart, right? Really competent. They have a professional expertise that's up here, but they have a communications expertise that's way down here. How do you explain the absence of rhetoric or public - what is the role - how do you see public speaking being either taught or the role that it plays? And because I feel like I also - I never - nobody ever named this as something that I should learn or do and I think the only - I have really vivid memories of an art history class, which was an elective in college in which I had to do a presentation and it was the only time I think in my four years of college I had to do - I had to stand up in front of a class and say something and I had a full-fledged panic attack.

No, it's insane. It's the - almost every adult professional has to talk all the time, whether it's in meetings, or job interviews, or pitches, or presentations, or technical updates, or sales reports. There aren't that many jobs where you don't have to do this thing, and yet no one has taught in any comprehensive way how to do it, ever, at all. I always, when I do workshops, I show, look how much you know about writing. You know the noun versus the verb versus the participle and the whatever, and capital letters, and periods, grammar, you know when you're looking at a book, the table of contents, and the different chapter headings, and all - all of this visual and theoretical and technical stuff about writing, and you don't know any of it for speaking.

So what's weird is that for 2,000 years, all of that was taught. And everybody was taught how to understand speech, both listening and talking, how to organize it better, how to do it better, and then a couple hundred years ago, it became very uncool, and it just fell away, because we all fell in love with science.

Is that - I was going to ask what - talk to me about that transition, what happened?

From the beginning, when they first invented logic, when they first invented rhetoric, some people hated it. And they said, why would you need people - like, why would you need to teach people how to speak the truth? This just seems fancy, it seems artificial. I'm like yeah, we're artificial. We cook our food instead of eating it just as we found it. We brush our teeth instead of leaving our breath just as we found it. You know what I mean? We do a lot of artificial stuff every day to get through the day. And we're pretty glad that we do. But for some reason, this idea about being - about prepping your speech or grooming it, or like fussing with it or arranging - it seems no. You're going to mess with the authenticity. You're going to ruin it. So even Plato - it wasn't just weirdos - Plato fulminated against rhetoric.

Really?

This is taking Greek into the gutter - Greek democracy. This is ruinous - people who speak the truth. The truth should be self-evident. We don't need help with this. And Aristotle came along and said, no, that's not true because people are too dumb and demagogues are too crafty. And we need to teach regular good people how to see the wiles of demagogues and bad argument and cheap manipulative arguers. And we also need to arm the regular people, how to speak up and get their point across so they'll be drowned out. But from the very beginning of rhetoric, there was this argument, is rhetoric good or bad? And that really persisted. And when you look at it from a certain slant, it does just look like total bullshit. It looks like a false, specious quasi-science or whatever. It's a quasi-art that shouldn't be necessary and -

Why not? What do you mean it shouldn't be necessary? What's the - Express the two sides like - so we've been talking about rhetoric and persuasion and you know giving breathing life into the idea that you need to take responsibility for being understood. What's the - what's Plato's view on that? What's the full expression of the opposition to rhetoric?

At the time of Plato, there was this group called the Sophists, who were like the David Blaines of rhetoric or whatever. They would come along and do - turn it into a parlor trick, and they would take pleasure - they would do these performance art thingies that, where they would get people - they would - the point of the thing was, I'm gonna show you that good is really bad, and bad is really good. And they would do an hour-long monologue that was full of comedy and full of like fun talking and by the end of it they would have quote-unquote proven to the audience that good is bad and their whole point was words are bullshit. You know, it was Pythagoras who was one of the sophists who said man is the measure of all things. And so at the bottom of that is we don't know what objective reality is. The only thing that exists is what you can get people to believe. And we're trapped inside our own bubbles of subjectivity. We'll just never know. We'll just never really know anything. Even science is basically this huge weird construct based upon our irrational subjective insanity. And from a certain point of view, that's true. But from another point of view the NASA scientists who make rockets aren't making the fuel with subjective quantities, like they need - there is a - they're - they're - so those two poles are the two sides of that argument could go to war forever and neither side is right. But I guess Plato was good enough at saying, look. Any supposed art form that allows liars to get away with lying has to be bad, right? And he took it further than that and made a better argument than that. But that was basically the thing. Liars should not be able to get away with lying. Therefore, rhetoric is bad. And we should just let everybody leave this alone and everyone will just be themselves. And we'll trust that the truth will always come out. And that's - I like that. I'm from Minnesota. We - that's how we function. That's how we're born, basically, plain people, and unfortunately, it just doesn't work. And it's not a realistic worldview.

And so how did it disappear, this moment you said we discovered science, and rhetoric went away

It's more than just science. Christianity took over and was the dominant thing, and basically for a long time, learning was confined to Christianity. And in Christianity, they weren't into open conversation about absolutely everything. Conversations became more behind closed doors, and you couldn't just go out into the public square and start shrieking about how you didn't believe in Christianity. You couldn't just say that the church was bad. So that was one factor. Science, like I said, was another thing where just people started getting more obsessed with facts and they were achieving all these miracles with science. And so rhetoric just seemed like this very squishy - what is this? It's not a science. It's not quite an art form. It's almost an art form, but it just seemed like the softest skill of all and therefore useless. John Locke, the philosopher, was really anti-rhetoric. Basically, anytime anybody abused any political system, people would come along and say, See, this is rhetoric's fault. These liars who became tyrants, they all used words in a weird way, and it's rhetoric's fault. Therefore, let's abolish rhetoric. And so eventually, all those forces combined, and it just became uncool. Rhetoric got broken down into a few component parts, which were not very powerful on their own, like philology and even linguistics and you could even say semiotics certainly like enunciation and diction and all of these became things that were taught and none of them were that powerful on their own so we lost this overall study of persuasion.

I want to go back a little bit. You told this amazing story about your cousin who found love as a result of Toastmasters, right? So then you discovered Toastmasters and I know, and then, so what happens with you after that? What do you do with this discovery?

Once I discovered, I really realized this is - I don't know if I should say the answer to all my dreams, but the capacities, the qualities, whatever, the effect of all of this stuff is the most magical, cool, positive thing I've ever discovered. And I owed Random House a second book for a two-book deal that I had signed a million years before, and they were pissed at me for not delivering. And I had been submitting ideas that were really negative, and they said, no way, that's way too gloomy, we're not interested in that. So for a second, just to get them off my back, I said I could write about this Toastmasters thing and public speaking, and they immediately said yes. And I immediately regretted it, because it was way too positive. And I didn't want to write a how-to book, and I just, I didn't know how to write about this subject. But I did think, this is the most positive, interesting thing I've ever come across. And so very reluctantly, very slowly and clueless, I started writing a book and it took me 10 years to write the damn book. But the book is the prequel. It's not a how-to do public speaking book, but it's a questioning of, holy cow, this is so weird. This used to be the biggest thing in education. It was the cornerstone of all education. And now we don't even know what it is. And it also happens to be the most useful skill for having relationships and doing well at work. And it's pretty weirdly easy to learn. Why don't we learn this anymore? In the book, I make myself be the guinea pig, and I go to Minneapolis, where I'm from, and I join Toastmasters, and I go through their introductory curriculum and learn all this stuff. So I'm the hapless idiot clown going through and not understanding each of these lessons until I finally figure them out and learn them. At the same time, I'm digesting all this Greek and Roman stuff about rhetoric and public speaking. Which merges with Toastmasters instructions in a really cool, good way.

Is that right? Yeah. In what way?

Toastmasters is not trying to be deep or profound or intellectual at all. They want to keep it simple. It's very much, what does it say, the founder said it's a go at your own pace, it's a learn at your own pace kind of a program, and everything is just do this, think about this a little bit, do this. And then your group gives you feedback. But there's nothing a profound or there's nothing about the theory. They don't talk about verb tenses. They don't think - they don't talk deeply about our isolation or emotional stuff. But the Greeks had all of this really great profound stuff, which in the way that they wrote it was very practical and pragmatic. It wasn't trying to be deep, but it just happens to be deep anyway. If you combine those two things together, yeah, it's gangbusters.

Yeah. And what was your experience with Toastmasters? What was that like actually going in, going through?

I didn't do it in New York. I did it in Minneapolis because I knew that people would be much worse at connecting. They're just shyer. They're like Nordic, Scandinavian people by and large still, even though the population there has gotten a lot more mixed since when I was a kid, it's still pretty uptight compared to New York where people are more performative and people are more used to difference. Yeah. And so for just testing out my little theories about how do I learn to connect with people and how do other people learn to connect with people? It was a better place to do it, but it was agony because of that. The first, my first three Toastmasters speeches, they were just these very low stakes exercises, but I was shitting in my pants. I was just so - if public speaking normally made me anxious doing it in this very meta way where I'm the reporter and I'm writing a book and my income is dependent on my ability to write a book. But my ability to write the book is dependent on my ability to go to Toastmasters and deliver stupid little icebreaker speech or basic intro exercise. It was just a lot of pressure on going in there. And I was also studying myself to pieces like, really overanalyzing everything. It was like smoking pot and having a bad pot trip or something. I just was so self-conscious about every part of it that I was falling apart. It was very hard to observe myself doing it while also doing it.

Is that an exceptional experience? Or is that, cause I also feel like there's this, there's that stat that I always roll out that we don't - aren't there survey after survey that demonstrate that people fear public speaking more than death, like that -

All of that is false. All of that is - it's a quasi-scientific - that's a marketing company came up with in the 60s and they like had a control group of 20 people.

Oh, no.

Think about it. If you put a gun to your head and said, Peter, do you want to pull the trigger or do this next meeting that you have? Of course, you're going to do the meeting. So it's just bullshit. But the fact that it resonates does, I think, say a lot. But I think the paralyzing thing for most people is just the number of choices, the bewildering number of choices and that fundamental question of what am I going to say and how am I going to say it? Because when you start thinking about it, you have infinite options. And it's perfect - perfect context for a meltdown. Holy cow, I'm not even real. I'm not even me. It turns out I'm just cheap actor. And the moment you give me some choices about what I'm doing, I don't even know who to be. There's no fixed self here. I'm just this phony who goes through life getting by trying to be pleasant, but I don't even really know why I do any of this the way that it - so you know, of course that's enough to make anybody bat shit and it should like - you know so somewhere between never thinking about it ever again and studying it and getting conversant with those ideas and figuring it out for yourself, what's right for you, there's an interesting and productive course of action that really will make you happier because you'll be - it's just like you're the person you've quoted Fiona. There's - you do have a responsibility to help people understand you. And so unless you learn some of this stuff, how are you going to do that? You can't just will it and force yourself to do it by beating up on yourself. You have to learn some techniques.

You've helped me a ton personally. And and it's been a - it's been transformational, no question. I think about the relationship between public speaking and democracy and this is like a indulgent kind of a side because I think you and I've talked like I'm really into citizen assembly and there's a way in which the way that we - in my small town of Hudson, if you want to participate in a public meeting, you just have to do this thing, which I draw - which you just described as a - It's a horrifying, terrifying experience to stand up in your community of fellows and it's just say - let your hair grow to use your old metaphor, right? Just let it out. And of course, who's going to participate in a public meeting when the stakes are that high and nobody's been any - has done any preparation. And and so I think it's interesting that we've - that it - it showed up as a way that public speaking showed up with democracy and then it went away and now we're - and now we're in all the trouble that we're in.

That was absolutely what made me want to write the book and that's absolutely what kept me at it for 10 years is because I thought this stuff is so important. I think I psyched myself out because it was so important to me to get it right. And, but I do think just on the most basic level democracy is about everyone having a voice. And if none of us has a voice because we never learned how to use it because we never learned how to do it in school, how is democracy supposed to work? And I don't think it's a coincidence that we're in the trouble we're in and the fact that we stopped teaching public speaking. So really, up until a couple hundred years ago, everyone with an education learned about this stuff, and now no one does. And you could argue if everyone learned how to speak up and argue better, wouldn't it be even more of a mess than it is now? Cause like in Greece, they had a really rowdy disastrous democracy and they eventually crapped and burned. So you could say, is this stuff bad? But I think in the same way you could say is free market capitalism good or bad? Obviously free market capitalism isn't doing a great job right now of saving the environment and stuff like that. But if you had some kind of free market capitalism that works, that has some guardrails on it and it works for people and for the planet instead of just for corporations, I still believe that seems to have worked better than other systems and so with speech, I have just as an article of faith. I have to believe the same thing. It's better if we can all speak up than if no one can speak up and I might be wrong, but that's really the only thing I'm equipped to believe. And so it may be that when everyone speaks up, we just crash and burn. But I think that now what's going on is where everyone hides behind the internet and very few of us can speak up. It doesn't seem to be working very well. And the Surgeon General came out with a report last year that was like our crisis of disconnection or our crisis of loneliness or something. And so you chart every single measure of civic health - suicide rates, trust in neighbors, amount of time spent with friends, amount of time spent with family, number of acquaintances who are slightly different than you, trust in the courts, in Congress, in your teacher, in your neighbor, all of these things are just going down. And I, again, as an article of faith, believe that if we could all learn to speak up better and be better understood, that would be better than everyone walking around silently being pissed off that the world doesn't understand us.

So I think we've run near the end of time. And I guess the end - what do you say to somebody, because I feel like this is something that we don't think about. What do you say to the people who are listening, who wonder about their ability to communicate, their public speaking?

When I work with clients, I always run them through the same paces and it doesn't really matter what they're preparing for. But the first step is always think about your audience. Who are you talking to? So I might have 10 gigabytes worth of information in my head. But if I'm talking to this type of person or that type of person, they only need to know a couple of megabytes of that information. So how do I dial down and curate or edit out the 99 percent of the stuff I know that you don't need to know. So if you're Polish or if you're old or you're young or you're this or you're that determines everything about what you need to know from me or what you want to know from me. So if I get rid of that 99 percent of my information before I talk to you, that makes it so much easier for me to talk to you. And it also makes me stop babbling and start talking to you like a person. You're an old Polish conservative who's only interested in blah blah blah. Okay, that's very different than a fourth grader who - you know what? Just yeah instead of me walking around with this huge head of steam. Oh my god I know so much stuff. I've got to tell everybody all of it, right? Here's what you need to know and that keeps me from babbling and it makes it so you get what you need. And then you like me more and we connect more and we walk away you having had a better interaction. So that's the first thing. The second thing is always just figure out what you want people to know or do as a result of what you said. So I want this old Polish conservative person to, I don't know, vote for my environmental policy or come to my hot dog store or whatever. Great. That's why I'm talking. Anything that I'm saying to you that doesn't assist with that aim is not necessary. It's a waste of time. It's going to make that person bored. It's going to give me too much to talk about, too much to think about. And then that will make me nervous and anxious. So those two thingies dial it down to something manageable. And all the work I do with people comes down to that.

I feel like that second question is always harder than one might think. Yes, they don't really always have an idea. I don't really - not like I guess it revealed to me the degree to which I'm really only thinking about the things that I want to talk about because I just want to talk about these things. I want to spend time with these ideas. I've any - I've totally forgotten you're there.

It's really antisocial. So at first when I heard that was a Toastmasters thing. Actually, what is your purpose? For talking, ask yourself what you want your audience to know or do is - I thought it was Machiavellian and horrible. Like I'm not some Svengali who's trying to get everyone to do what I want them to do. I'm just this cool writer who has information to share. The idea that is totally wrong. And the idea that's even antisocial was profound. How is it antisocial? Because if I think that you're just going to sit there passively for half an hour listening to me talk about my book and there's no social transaction going on between us. I don't want you to believe anything. I just want to share my facts. That's bullshit. It's superficial and it's not realistic. I want you to know about my book about slavery so that you vote for some policies that will protect farm workers or you vote for my policy or you go to some website where there's a farm worker labor rights group and you give them money or you buy my book or whatever but I want you to do something. And so once I start to think about what I want you to do, I'm then thinking about you. Oh, Peter doesn't have the money to buy my book, or Peter doesn't have the time to go to the website I want him to go to. Great, I have to think about the reality of your life. Why don't you have the time? How can I get you to understand that it's going to help you to find the time? And so I start thinking about you a lot more, and me and my facts a lot less. And that's the magic of public speaking. That's the way that we connect to people, shockingly, is to start thinking about other people instead of our head full of information. Yeah.

I want to talk about my favorite client of all time. This guy came to me. It was very smart. Short foreign guy working for a big huge fortune 50 bank and he was in a very technical part of the operation and he said his boss - everyone liked him but his boss said you talk too much and you're bumming people out because you talk too much and he came to me. He said I know that this is a real thing. Can you help me solve it? And I said I can try, let's see. So we went through those same two paces that we've talked about. Who's your audience and what do you want them to know or do? And just going through that, I - I said, what is your purpose? Because it seemed to me like he was trying to show off. He wanted everyone to think he was smart and that - when I wrote my book, I realized I had a similar thing where I was always pursuing this agenda of wanting everyone to think I was really interesting and original. And once you realize they don't care, they want to know something else, then that puts you on a very different track for how you're going to talk to them. So with this guy, he realized, yeah, I don't want them to think I'm short or foreign, I just want them to think I'm smart because I am smart. I said there's a better way for you to demonstrate that. And, maybe we worked together for six hours and he totally got over that problem. And then he went to his boss and he said, I got over that problem. Now promote me. Cause I'm a couple levels down lower than I should be. And you guys are always talking about your DEI stuff, promote me. And they started hemming and hawing. And so he said forget you. And he just went and interviewed at some other bank and he got a job there, two levels higher, but all of this was because he didn't know how to talk to people well, and he was actively offending people or distracting them or bumming them out with the way he talked, even though he was a really likable and smart guy.

Yeah, I'm remembering too in some of our previous conversations you talk about - there's like a myth of confidence that it's a problem of confidence, right?

That's great. Every other public speaking coach out there or trainer or whatever they spent a lot of time talking about anxiety and confidence, and the reason you can't do this is because you're anxious. We'll teach you how to be less anxious and more confident. And the Romans and the Greeks taught all of this stuff for 2,000 years with no mention of that. The anxiety is not the problem, the fact that you don't know how to use words or rhetoric is the problem. Once you know how to use words and rhetoric better, and make your points better, it'll work better. And then you'll have confidence that actually, yes, you do know how to do this. And you don't have some psychological condition that is permanent, that is keeping you from doing it well. You have literally millions of people walking around thinking that they're mentally ill when really they just lacked some basic training in this stuff.

Yeah. Yeah. It's remarkable. And I'm complicit in my spreading of that public speaking fear of public speaking more than death. Yeah, I should really think about that. I won't say it ever again because I want you to think I'm smart.

And I do.

All right. So we've run at the end of time John. Thank you so much. This has been a lot of fun. I appreciate it.

Thank you too Peter. It was super fun.